Theory of Mind in Multi-Agent LLM Collaboration - An Important Aspect on Collective Intelligence

24 Jul 2025

Introduction

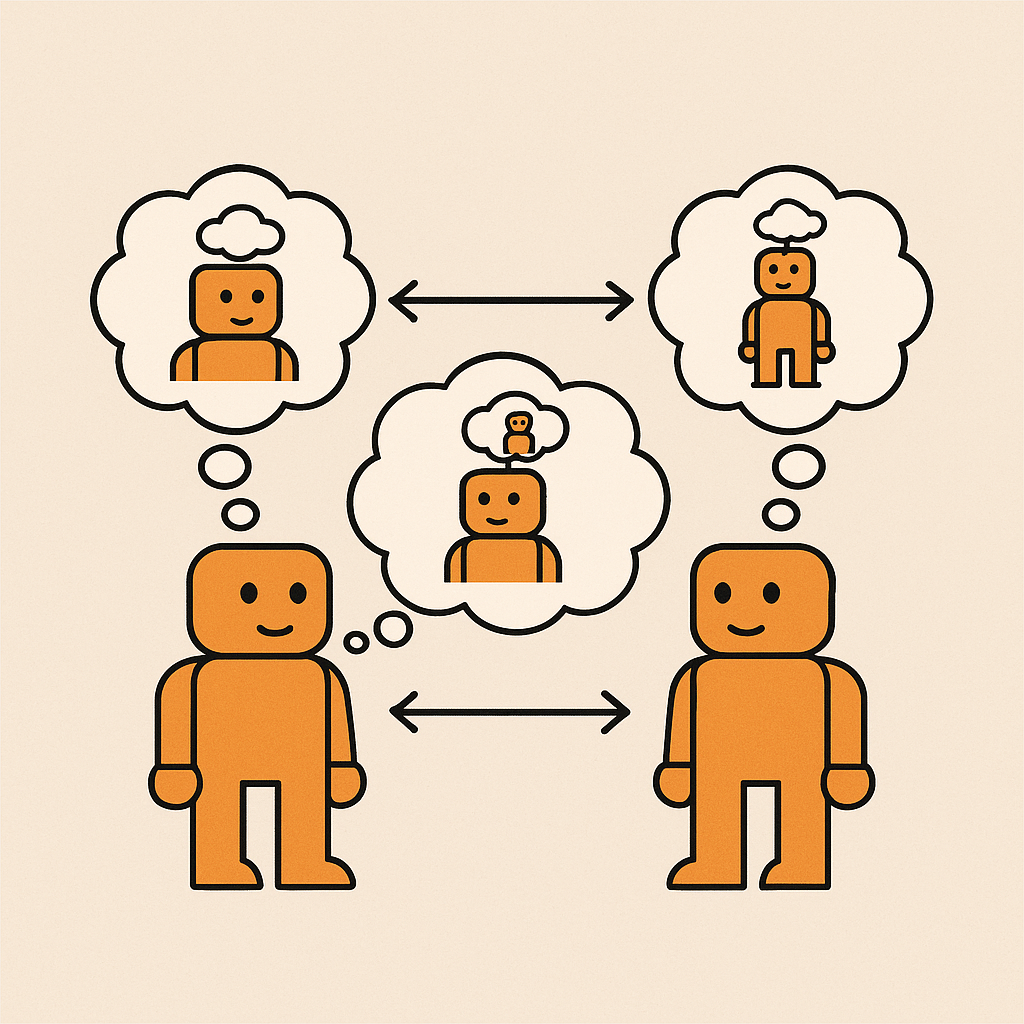

As advancements in LLM reasoning capabilities push the boundaries of AI agents toward more complex problem-solving, group intelligence has become a focal point of science exploration since we started to host WMAC workshops (https://multiagents.org). The emergence of large language models (LLMs) as cognitive agents has opened unprecedented opportunities for multi-agent collaboration. However, effective coordination between autonomous agents requires more than just linguistic competence, it demands the capacity to model, predict, and reason about the mental states of other agents. This cognitive ability, known as theory of mind, in my opinion prerequisites for sophisticated collaborative behavior.

In human cognition, theory of mind enables us to attribute beliefs, desires, intentions, and knowledge to others, forming the foundation for strategic interaction, communication, and collective problem-solving. When applied to LLM-driven agents, this raises important questions about how artificial systems might develop similar metacognitive capabilities and leverage them to improve collaborative performance.

This post provides a brief introduction to theoretical frameworks, computational architectures, and empirical challenges associated with implementing theory of mind in MAC systems, with particular emphasis on how such capabilities may lead to emergent collective intelligence.

Theoretical Foundations

Classical Theory of Mind

Theory of mind research traditionally focuses on hierarchical belief structures. At the most basic level, first-order ToM involves understanding that others have beliefs different from one’s own. Second-order ToM extends this to beliefs about beliefs (“Alice believes that Bob thinks the meeting is at 3pm”), and higher-order ToM continues this recursive structure.

Formally, an agent $A$’s belief about agent $B$’s belief state can be represented as:

\[\text{Bel}_A(\text{Bel}_B(\phi))\]where $\phi$ represents a proposition about the world state. This recursive belief modeling becomes computationally challenging as the depth increases, leading to what cognitive scientists call the “curse of recursion” in ToM reasoning.

Computational Theory of Mind for LLMs

For LLM-driven agents, classical ToM frameworks can be extended to account for the unique characteristics of transformer-based cognition. Unlike humans, LLMs process information through attention mechanisms and contextual embeddings, suggesting that their theory of mind might emerge from different computational principles.

One proposed framework is the Distributed Belief State Model, where each agent $A_i$ maintains:

- Self-model: $M_i^{\text{self}}$ – an internal representation of its own capabilities, goals, and knowledge

- Other-models: $M_i^{j}$ – beliefs about other agents $A_j$’s mental states

- Meta-models: $M_i^{j,k}$ – beliefs about agent $A_j$’s beliefs about agent $A_k$

This model draws on LLMs’ pre-trained knowledge of human psychology and social reasoning to bootstrap theory of mind capabilities rather than acquiring them solely through interaction.

Even before the emergence of LLMs, it’s not rare for machine learning systems such as conventional task-oriented dialogue systems to encorporate belief states. However, the belief states in ToM are much more dynamic, probalistic and active updating due to new observations.

Architectures for Multi-Agent ToM

Centralized vs. Decentralized Approaches

In the literature, centralized ToM architectures maintain comprehensive models of all agents’ mental states within a single coordinating agent. This is computationally efficient for small groups but lacks scalability and robustness.

By contrast, decentralized architectures allow each agent to independently develop ToM through direct interaction and observation. This more closely resembles human social cognition but imposes greater coordination complexity.

A Hierarchical Hybrid Architecture has been proposed to balance these trade-offs:

Level 3: Global Coordinator (high-level goal alignment)

Level 2: Local Coordinators (domain-specific collaboration)

Level 1: Individual Agents (direct interaction and ToM)

Attention-Based ToM Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms in LLMs can be adapted for ToM reasoning. Some studies suggest incorporating Social Attention Layers that specifically attend to:

- Belief-relevant tokens – language indicating other agents’ mental states

- Perspective markers – linguistic cues about viewpoints and knowledge boundaries

- Intentionality signals – expressions of goals, plans, and strategic thinking

In these models, attention weights are interpreted as probabilistic confidence in mental state attributions (Li et al., 2024):

\[\alpha_{i,j} = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{q_i^{\text{ToM}} \cdot k_j^{\text{belief}}}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)\]where $q_i^{\text{ToM}}$ represents a theory of mind query vector and $k_j^{\text{belief}}$ represents belief-state key vectors.

Empirical Challenges and Measurement

Benchmarking Multi-Agent ToM

Traditional ToM assessments (false-belief tasks, Sally-Anne test) are insufficient for evaluating sophisticated MAC. More advanced benchmarks are required to evaluate:

- Dynamic belief updating in response to new information

- Strategic deception and trust in competitive/cooperative scenarios

- Collective reasoning where agents must coordinate mental models

- Communication efficiency enabled by shared ToM understanding

New benchmarks such as HI-TOM (He et al., 2023) and those discussed by Wu et al. (2024) aim to capture these dimensions.

The Emergence Problem

A key research question is whether ToM can emerge from LLM interaction or must be explicitly trained. Preliminary evidence indicates that LLMs exhibit surprising ToM abilities in zero-shot settings, though scaling these abilities to robust MAC remains an open challenge.

Some researchers suggest that emergent ToM may follow a phase transition dynamic, where collaborative capabilities increase sharply beyond a threshold of agent interaction and complexity.

Applications and Future Directions

Collaborative Problem-Solving

MAC systems with robust ToM capabilities could enhance coordinated intelligence across various domains:

- Scientific Research: Agents specializing in different disciplines collaborating on complex problems

- Software Development: Teams of coding agents with complementary expertise

- Strategic Planning: Agents modeling different stakeholder perspectives in policy design

Alignment and Safety Considerations

Theory of mind in AI systems raises important safety considerations. Agents capable of modeling mental states may:

- Manipulate human users through targeted psychological influence

- Deceive other AI systems in competitive contexts

- Form adversarial coalitions that undermine human interests

Research into Aligned Theory of Mind must ensure that ToM capabilities enhance rather than subvert human values and objectives (Street, 2024).

Conclusion

Theory of mind represents a crucial frontier in MAC. As LLM capabilities continue advancing, developing sophisticated ToM mechanisms may determine whether artificial agents can achieve truly human-like collaborative intelligence or remain limited to surface-level coordination.

Progress will depend on interdisciplinary efforts from cognitive science, AI research, and ethics to ensure that artificial theory of mind serves collective human goals. Future research should prioritize:

- Empirical validation of ToM mechanisms in realistic MAC tasks

- Development of safety and alignment frameworks for ToM-enabled systems

- Exploration of how artificial ToM might complement human cognition

The emergence of truly collaborative artificial intelligence may depend not just on computational power—but on the capacity to understand and reason about minds, artificial and human alike.

References

- Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(4), 515–526.

- Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children’s understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance–reality distinction. Child Development, 59(1), 26–37.

- Kosinski, M. (2024). Evaluating Large Language Models in Theory of Mind Tasks. arXiv:2302.02083.

- Li, H., Chong, Y. Q., Stepputtis, S., Campbell, J., Hughes, D., Lewis, M., & Sycara, K. (2024). Theory of Mind for Multi-Agent Collaboration via Large Language Models. arXiv:2310.10701.

- Lewis, P. A., Dunbar, R. I. M., Berry, D. S., & Smith, R. I. (2017). Higher-order intentionality tasks are cognitively more demanding. Scientific Reports, 7, 14809.

- Ullman, T. D., Spelke, E., Battaglia, P., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2017). Mind Games: Game Engines as an Architecture for Intuitive Physics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(9), 649–665.

- Chen, R., Zhang, L., & Wang, X. (2025). Theory of Mind in Large Language Models. arXiv:2505.00026.

- Street, W., Johnson, K., & Rao, M. (2024). LLMs Achieve Adult Human Performance on Higher-Order Theory of Mind. arXiv:2405.18870.

- Street, W. (2024). LLM Theory of Mind and Alignment: Opportunities and Risks. arXiv:2405.08154.

- Wu, Y., Huang, J., & Liu, Y. (2024). Benchmarking Theory of Mind in Large Language Models. arXiv:2402.15052.

- He, Y., Zhang, S., & Luo, Z. (2023). HI-TOM: A Benchmark for Evaluating Higher-Order Theory of Mind. arXiv:2310.16755.

- Riemer, M., Gupta, A., & Chen, D. (2024). Theory of Mind Benchmarks Are Broken for Large LLMs. arXiv:2412.19726.

This post represents ongoing research in computational theory of mind. Welcome further discussion, pls reach out to me